Agility might be the most misunderstood concept in the performance field as our profession lacks a thorough understanding of its meaning and its application.

Over the past 40-years, agility has run through the musical chairs of definitions. Since the 70s, we’ve used phrases such as:

Currently, the most accepted definition today is:

“A rapid, whole-body change of direction and speed in response to a stimulus” - Sheppard & Young, 2006

But even this definition leaves a lot to be desired and misses the boat on a number of important pieces (which we’ll get into).

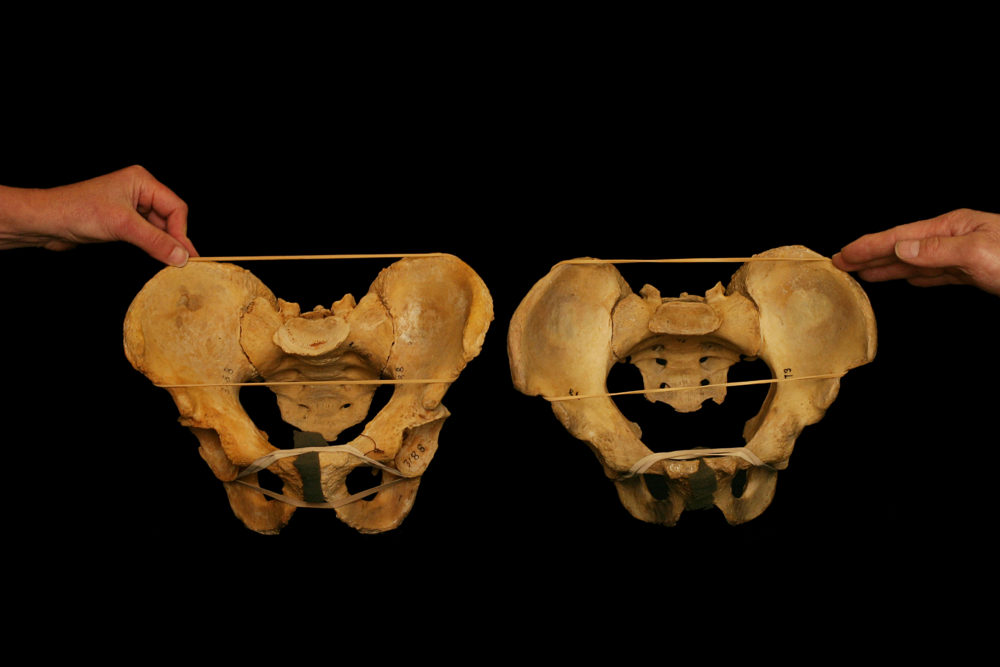

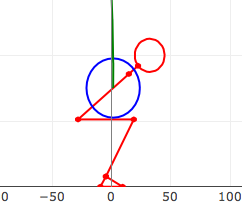

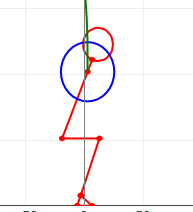

Strength and conditioning specialists will typically look at agility through the lens of physical abilities: strength qualities, eccentric/isometric qualities, and reactive strength.

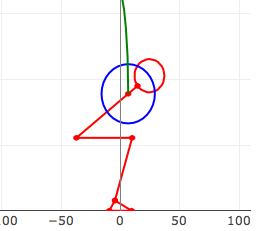

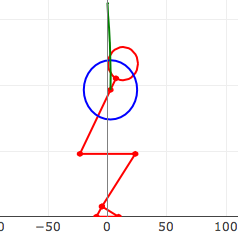

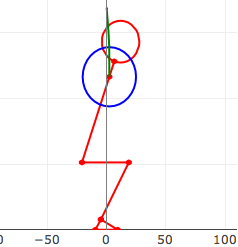

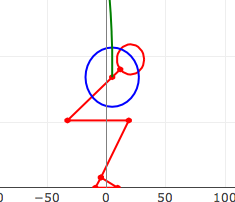

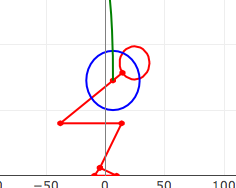

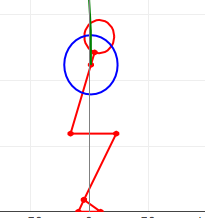

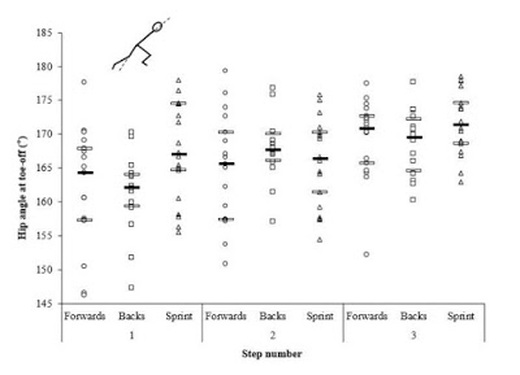

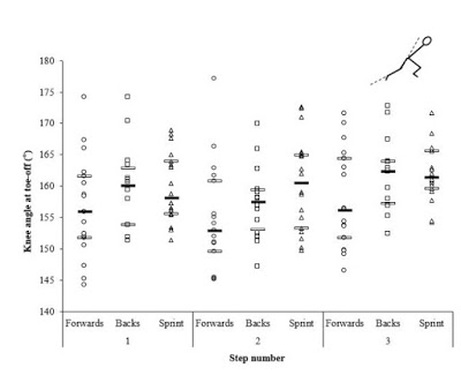

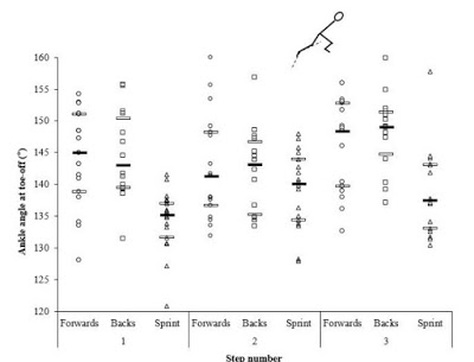

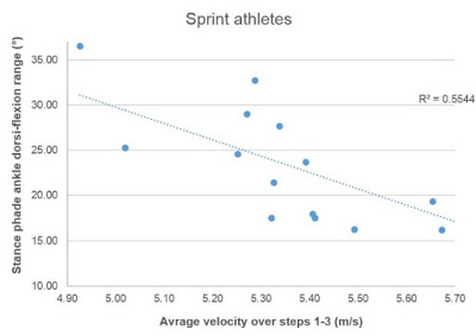

Pair this with most S&C’s education involving a big piece on biomechanics and you’ll see a large influence on a mechanical and technical model of joint angles, specific body positioning, foot placement, and kinematic/kinetic data driving feedback.

You can see this biomechanical bias with the need for coaches to categorize and label movement into terms like crossover step, side-step, split-step, hip turn, directional step, power cut, etc. and then use these to build their “movement” library.

This is an exercise of futility and only works to water down and miss the complex nature of the athlete-environment relationship.

With this in mind, it’s imperative to remember that agility lives within a specific context, and without that context, there is no agility. So agility is NOT a singular bio-motor that one possesses or not, it depends on the context in which it’s being asked.

This is where the current definition of, “in response to a stimulus”, leaves a lot to be desired.

It’s not about a response to just any stimulus, rather it’s about the pick-up of specifying information from the athlete’s specific sporting environment to guide movement behavior.

I often think about the following quote when it comes to agility or better put, sport movement,

“Everyone is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

If we try to judge an athlete’s agility, outside of the context and environment in which they’ll be asked to perform, you’re not testing their agility.

Just as an NFL wide receiver may possess incredible agility on an NFL Sunday, place that same athlete on a soccer pitch and they’ll look like a fish trying to climb a tree.

Or if we ask an offensive lineman to play wide receiver their “agility” will clearly be lacking. BUT if you watched that offensive lineman all game, both in run blocking and pass protection, there is no doubt you’d come away saying they possess great agility to be able to pull out in front of their running back to kick out a linebacker, or to pass set on a speedy defensive end, or to handle a stunt with ease.

There is a reason athletes play and specialize in certain positions (offense vs defense) as they are better equipped to handle the information and tasks of each.

For instance, watch a basketball game, on one end of the court an athlete will look amazing as they blow by a defender for a dunk, then on the other end, they’ll struggle to stay in front of the player they just burned.

Hopefully, you can start to see how we must change the lens in which we view sport movement. If we truly think a 505 or L-Drill or star drill is capturing the essence of agility, you’ll be disappointed.

To really capture this process, we need to appreciate the environment in which movement will organize and emerge. So going back, there is no singular definition or drill that can capture agility, it all depends on the task and performance environment.

So what does all this mean?

First, we have to respect the environment as much as we respect the athlete themselves. The athlete is always performing in an environment; the athlete and that environment are always linked and their relationship is mutual. So in my opinion agility has to start with an environment.

Second, that environment should seek to preserve the key specifying information variables from sport. To make agility stick and transfer to sport, coaches must ensure the information in their training activities is similar to what they’ll encounter in the game.

So think about variables like space, time, opponent(s), equipment, rules, situations, and intentions of the game environment and see if you can maintain some essence of those in your training activities.

Lastly, as stated early, agility is not something that one possesses and owns; it’s an ongoing and continually adapting process. Athletes don’t actually acquire the skill of agility; rather athletes gain experience of adapting and picking-up specifying information (becoming more attuned) and then organizing and scaling movement solutions to this specifying information (calibration).

With all this mind and with the framework of viewing agility not only through a movement pattern lens, but also an environmental/task lens.

Over the past 40-years, agility has run through the musical chairs of definitions. Since the 70s, we’ve used phrases such as:

- Ability to change direction rapidly

- Ability to change direction rapidly and accurately

- A whole-body change of direction and speed

Currently, the most accepted definition today is:

“A rapid, whole-body change of direction and speed in response to a stimulus” - Sheppard & Young, 2006

But even this definition leaves a lot to be desired and misses the boat on a number of important pieces (which we’ll get into).

Strength and conditioning specialists will typically look at agility through the lens of physical abilities: strength qualities, eccentric/isometric qualities, and reactive strength.

Pair this with most S&C’s education involving a big piece on biomechanics and you’ll see a large influence on a mechanical and technical model of joint angles, specific body positioning, foot placement, and kinematic/kinetic data driving feedback.

You can see this biomechanical bias with the need for coaches to categorize and label movement into terms like crossover step, side-step, split-step, hip turn, directional step, power cut, etc. and then use these to build their “movement” library.

This is an exercise of futility and only works to water down and miss the complex nature of the athlete-environment relationship.

With this in mind, it’s imperative to remember that agility lives within a specific context, and without that context, there is no agility. So agility is NOT a singular bio-motor that one possesses or not, it depends on the context in which it’s being asked.

This is where the current definition of, “in response to a stimulus”, leaves a lot to be desired.

It’s not about a response to just any stimulus, rather it’s about the pick-up of specifying information from the athlete’s specific sporting environment to guide movement behavior.

I often think about the following quote when it comes to agility or better put, sport movement,

“Everyone is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

If we try to judge an athlete’s agility, outside of the context and environment in which they’ll be asked to perform, you’re not testing their agility.

Just as an NFL wide receiver may possess incredible agility on an NFL Sunday, place that same athlete on a soccer pitch and they’ll look like a fish trying to climb a tree.

Or if we ask an offensive lineman to play wide receiver their “agility” will clearly be lacking. BUT if you watched that offensive lineman all game, both in run blocking and pass protection, there is no doubt you’d come away saying they possess great agility to be able to pull out in front of their running back to kick out a linebacker, or to pass set on a speedy defensive end, or to handle a stunt with ease.

There is a reason athletes play and specialize in certain positions (offense vs defense) as they are better equipped to handle the information and tasks of each.

For instance, watch a basketball game, on one end of the court an athlete will look amazing as they blow by a defender for a dunk, then on the other end, they’ll struggle to stay in front of the player they just burned.

Hopefully, you can start to see how we must change the lens in which we view sport movement. If we truly think a 505 or L-Drill or star drill is capturing the essence of agility, you’ll be disappointed.

To really capture this process, we need to appreciate the environment in which movement will organize and emerge. So going back, there is no singular definition or drill that can capture agility, it all depends on the task and performance environment.

So what does all this mean?

First, we have to respect the environment as much as we respect the athlete themselves. The athlete is always performing in an environment; the athlete and that environment are always linked and their relationship is mutual. So in my opinion agility has to start with an environment.

Second, that environment should seek to preserve the key specifying information variables from sport. To make agility stick and transfer to sport, coaches must ensure the information in their training activities is similar to what they’ll encounter in the game.

So think about variables like space, time, opponent(s), equipment, rules, situations, and intentions of the game environment and see if you can maintain some essence of those in your training activities.

Lastly, as stated early, agility is not something that one possesses and owns; it’s an ongoing and continually adapting process. Athletes don’t actually acquire the skill of agility; rather athletes gain experience of adapting and picking-up specifying information (becoming more attuned) and then organizing and scaling movement solutions to this specifying information (calibration).

With all this mind and with the framework of viewing agility not only through a movement pattern lens, but also an environmental/task lens.

If you enjoyed this,

check out my Agility Mini Course through Emergence.

Truly feel this 90min course is the

most thorough discussion surrounding agility.

https://emergentmvmt.com/product/agility/

check out my Agility Mini Course through Emergence.

Truly feel this 90min course is the

most thorough discussion surrounding agility.

https://emergentmvmt.com/product/agility/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed