For anyone that has done research or submitted to a journal, knows the amount of time, detail, revisions, and head-ache that goes into writing and researching for a paper.

Writing a proposal, getting proposal approval, getting IRB approval, collecting subjects, data collection, data analysis, submission to journals, rejection, another submission, revisions, re-submission, more revisions, re-submission, and finally acceptance. This process can take anywhere fem 6-18months from start to finish; not to mention the tons of stress and time and loss of confidence that comes from writing, sifting through hundreds of research articles, inevitable rejection, double digit revisions, and wondering if your work will ever be accepted.

For those of us who are full-time coaches, it is difficult to find the time and energy to dedicate to this type of consistent research.

With that being said, I do think every S&C coach should strive to produce a real scientific paper and be published by a journal.

There are a couple of reasons for this.

While I do enjoy the process and the opportunity to have work published, I also know there is simply not enough hours in the day to get all the data I track published into a journal.

So instead, I will label articles in this section as BBA Journal of Sports Performance. This will be where I can dump research that we're conducting at BBA, but aren't working to get published into a journal.

With that being said, this work will all be conducted in a scientific manner - clean procedures, proper set-up, detailed data collection, and inferential data analysis. There will be less detailed introductions and discussions - just want to present the data with a few closing thoughts.

The overall goal is for this data to be more than anecdotal or what another pet peeve of mine is when coaches say, "We've seen great results from INSERT EXERCISE/TOOL/MODALITY". Yet, they cannot produce results, a control group, or inferential statistics to validate their claims.

So without further ado, let's go into this BBA Journal Study.

Writing a proposal, getting proposal approval, getting IRB approval, collecting subjects, data collection, data analysis, submission to journals, rejection, another submission, revisions, re-submission, more revisions, re-submission, and finally acceptance. This process can take anywhere fem 6-18months from start to finish; not to mention the tons of stress and time and loss of confidence that comes from writing, sifting through hundreds of research articles, inevitable rejection, double digit revisions, and wondering if your work will ever be accepted.

For those of us who are full-time coaches, it is difficult to find the time and energy to dedicate to this type of consistent research.

With that being said, I do think every S&C coach should strive to produce a real scientific paper and be published by a journal.

There are a couple of reasons for this.

- We have access to real athletes - something a lot of research is missing

- Give back and further the education of our field

- Appreciate and understand of how difficult, tedious, and in-depth research can be. It's a pet peeve of mine when coaches, who have never published research, criticize those that do. You'll be humbled when you go through this process

While I do enjoy the process and the opportunity to have work published, I also know there is simply not enough hours in the day to get all the data I track published into a journal.

So instead, I will label articles in this section as BBA Journal of Sports Performance. This will be where I can dump research that we're conducting at BBA, but aren't working to get published into a journal.

With that being said, this work will all be conducted in a scientific manner - clean procedures, proper set-up, detailed data collection, and inferential data analysis. There will be less detailed introductions and discussions - just want to present the data with a few closing thoughts.

The overall goal is for this data to be more than anecdotal or what another pet peeve of mine is when coaches say, "We've seen great results from INSERT EXERCISE/TOOL/MODALITY". Yet, they cannot produce results, a control group, or inferential statistics to validate their claims.

So without further ado, let's go into this BBA Journal Study.

EFFECT OF VARIOUS POST-ACTIVATION POTENTIATION

TECHNIQUES ON COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP

TECHNIQUES ON COUNTERMOVEMENT JUMP

INTRODUCTION:

Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP) is the concept of applying a conditional activity (CA) to improve the proceeding activity. Great sport scientist Yuri Verhoshansky was the first to describe the effects of PAP and investigate them in a chronic training program (7). Verkhoshansky recommended performing explosive and plyometric movements after resistance movement to take advantage of the possible heightened excitability of the central nervous system.

While Verkhoshansky generally stated "heightened" excitability - the exact mechanisms that effect PAP are not 100% quantified, but it's likely a combination of muscular and neural interplay. Increased neural activity may occur through recruitment and synchronization of motor units, a decrease in presynaptic inhibition, or import more central nerve impulses (3). A CA may also lead to the phosphorylation of myosin regulation light chains (4,5). This mechanism is mainly attributed to actin-myosin interaction via Ca2+ released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (6). Myosin light chain kinase, which is responsible for making more ATP available at the actin-myosin complex increases the rate of actin-myosin cross-bridging. This leads the CA to increase the power output of the cross bridges and this in turn improves the performance of explosive movements (6).

In basic terms, the idea of PAP is to stimulate or excite the nervous and muscular system to improve the RFD, power, and speed of the following activity. The CA can be anything from heavy loaded lifts, power movements, or elastic activities.

PAP has been heavily studied, and overall PAP has been shown to be effective, but with many caveats. Seitz et al. (2015) did a meta-analysis on PAP factors on jumping, sprinting, throwing, and upper-body ballistic performance (1). The researchers reviewed all pertaining research and found the following trends to be effective for PAP performance.

For these reasons, you'll likely see the implementation of PAP strategies within a sports performance environment. The meta-analysis from Seitz et al. (2015) showed the benefits from a CA of plyometrics on the proceeding activity, but previous literature is heavily favored towards the CA being a resistance training movement such as moderate to heavy back squats. To further investigate this plyometric effect, this study hopes to examine three different variations of plyometric activity - resisted, assisted, and depth jump.

Band assisted CMJ training was shown to be more effective than traditional BW CMJ training in high level volleyball players (1). These researchers concluded that assisted jumping may promote the leg extensor musculature to undergo a more rapid rate of shortening, and chronic exposure appears to improve jumping ability (1).

SUBJECTS:

Twenty-one male, collegiate baseball athletes (age=20.33) partook in this study. There were three groups of five subjects, and one group of six subjects. All subjects had at least 1-year of resistance training in a S&C program (avg=2.23years)

PROCEDURES:

Participants were randomly split into 4 groups (n=5; n=5; n=5; n=6). Over the course of 2-weeks (Week 1 = Mon, Fri; Week 2 = Mon, Fri) participants came in and were tested. Each testing day, each group underwent one of four conditions - Depth Jump (DJ), Band Resisted CMJ (Rest), Band Assisted CMJ (Asst), or Control (Con). Each group was subjected to each of the four conditions over the four testing days.

After performing the same dynamic warm-up each day, each group followed the below procedures. Each group was given the same instructions - "Jump as high as you can and also as fast as you can off the ground".

Post-Activation Potentiation (PAP) is the concept of applying a conditional activity (CA) to improve the proceeding activity. Great sport scientist Yuri Verhoshansky was the first to describe the effects of PAP and investigate them in a chronic training program (7). Verkhoshansky recommended performing explosive and plyometric movements after resistance movement to take advantage of the possible heightened excitability of the central nervous system.

While Verkhoshansky generally stated "heightened" excitability - the exact mechanisms that effect PAP are not 100% quantified, but it's likely a combination of muscular and neural interplay. Increased neural activity may occur through recruitment and synchronization of motor units, a decrease in presynaptic inhibition, or import more central nerve impulses (3). A CA may also lead to the phosphorylation of myosin regulation light chains (4,5). This mechanism is mainly attributed to actin-myosin interaction via Ca2+ released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (6). Myosin light chain kinase, which is responsible for making more ATP available at the actin-myosin complex increases the rate of actin-myosin cross-bridging. This leads the CA to increase the power output of the cross bridges and this in turn improves the performance of explosive movements (6).

In basic terms, the idea of PAP is to stimulate or excite the nervous and muscular system to improve the RFD, power, and speed of the following activity. The CA can be anything from heavy loaded lifts, power movements, or elastic activities.

PAP has been heavily studied, and overall PAP has been shown to be effective, but with many caveats. Seitz et al. (2015) did a meta-analysis on PAP factors on jumping, sprinting, throwing, and upper-body ballistic performance (1). The researchers reviewed all pertaining research and found the following trends to be effective for PAP performance.

- A larger PAP effect is observed among stronger individuals and those with more experience in resistance training

- Plyometric (ES = 0.47) CAs induce a slightly larger PAP effect than traditional high-intensity (ES = 0.41), traditional moderate-intensity (ES = 0.19), and maximal isometric (ES = -0.09) CAs

- Greater effect after shallower (ES = 0.58) versus deeper (ES = 0.25) squat CAs, longer (ES = 0.44 and 0.49) versus shorter (ES = 0.17) recovery intervals, multiple- (ES = 0.69) versus single- (ES = 0.24) set CAs, and repetition maximum (RM) (ES = 0.51) versus sub-maximal (ES = 0.34) loads during the CA.

- It is noteworthy that a greater PAP effect can be realized earlier after a plyometric CA than with traditional high- and moderate-intensity CAs. Additionally, shorter recovery intervals, single-set CAs, and RM CAs are more effective at inducing PAP in stronger individuals, while weaker individuals respond better to longer recovery intervals, multiple-set CAs, and sub-maximal CAs.

- Both weaker and stronger individuals express greater PAP after shallower squat CAs.

- Performing a CA elicits small PAP effects for jump, throw, and upper-body ballistic performance activities, and a moderate effect for sprint performance activity.

- The level of potentiation is dependent on the individual's level of strength and resistance training experience, the type of CA, the depth of the squat when this exercise is employed to elicit PAP, the rest period between the CA and subsequent performance, the number of set(s) of the CA, and the type of load used during the CA.

- Finally, some components of the strength-power-potentiation complex modulate the PAP response of weaker and stronger individuals in a different way.

For these reasons, you'll likely see the implementation of PAP strategies within a sports performance environment. The meta-analysis from Seitz et al. (2015) showed the benefits from a CA of plyometrics on the proceeding activity, but previous literature is heavily favored towards the CA being a resistance training movement such as moderate to heavy back squats. To further investigate this plyometric effect, this study hopes to examine three different variations of plyometric activity - resisted, assisted, and depth jump.

Band assisted CMJ training was shown to be more effective than traditional BW CMJ training in high level volleyball players (1). These researchers concluded that assisted jumping may promote the leg extensor musculature to undergo a more rapid rate of shortening, and chronic exposure appears to improve jumping ability (1).

SUBJECTS:

Twenty-one male, collegiate baseball athletes (age=20.33) partook in this study. There were three groups of five subjects, and one group of six subjects. All subjects had at least 1-year of resistance training in a S&C program (avg=2.23years)

PROCEDURES:

Participants were randomly split into 4 groups (n=5; n=5; n=5; n=6). Over the course of 2-weeks (Week 1 = Mon, Fri; Week 2 = Mon, Fri) participants came in and were tested. Each testing day, each group underwent one of four conditions - Depth Jump (DJ), Band Resisted CMJ (Rest), Band Assisted CMJ (Asst), or Control (Con). Each group was subjected to each of the four conditions over the four testing days.

After performing the same dynamic warm-up each day, each group followed the below procedures. Each group was given the same instructions - "Jump as high as you can and also as fast as you can off the ground".

- DJ Group = 2x5 Depth Jumps off a 20" Box. Rest periods - 20sec between each rep; 2min between sets.

- Rest Group = 2x5 Band Resisted CMJ. Rest periods - Reps performed in a continuous action; 2min between sets.

- Asst Group = 2x5 Band Assisted CMJ. Rest periods - Reps performed in a continuous action; 2min between sets.

- Control = Went directly to CMJ testing.

RESULTS:

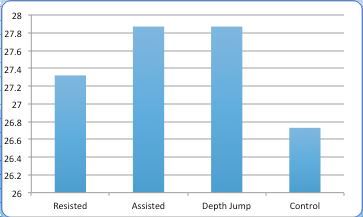

The use of paired T-Tests were used to test between each experimental groups to determine significance (p=0.05). The results are below.

- Depth Jump (DJ) was superior to Control (p=0.00)

- DJ was also superior to Resisted (p=0.00)

- DJ and Assisted had no statistical difference (p=0.217)

- Assisted was superior to Control (p=0.00)

- Assisted was also superior to Resisted (p=0.036)

- Resisted was superior to Control (p=0.003)

APPLICATION:

Given these results, a coach, athlete, or sport that requires great performance in the CMJ, may consider adapting a warm-up or conditioning activity that includes depth jumps or band assisted jumps. Even the use of band resisted jumps elicits superior results than doing nothing at all, but this route is inferior to both depth jumps and band assisted.

Sports or environments like track and field, volleyball, NFL combine, and NBA combine all may benefit from these results. It would also be beneficial for future research to evaluate the long-term effects of such training measures.

References:

1. Seitz, L. B., & Haff, G. G. (2015). Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Body Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine, 1-10.

2. Sheppard, J. M., Dingley, A. A., Janssen, I., Spratford, W., Chapman, D. W., & Newton, R. U. (2011). The effect of assisted jumping on vertical jump height in high-performance volleyball players. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 14(1), 85-89.

3. Tillin NA, Bishop D. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation and its Effect on Performance of Subsequent Explosive Activities. Sports Med. 39 (2): 147-166, 2009.

4. Rassier DE, MacIntosh BR. Coexistence of potentiation and fatigue in skeletal muscle. Braz. J. Med.Biol. Res. 33(5):499–508, 2000.

5. Rassier DE, MacIntosh BR. Coexistence of potentiation and fatigue in skeletal muscle. Braz. J. Med.Biol. Res. 33(5):499–508, 2000.

6. Christos, K. (2010). Post-activation potentiation: Factors affecting it and the effect on performance. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 28(3).

7. Verkhoshansky Y, Tetyan V. Speed-strength preparation of future champions. Legkaya Atleika. 2:12–13 , 1973.

Given these results, a coach, athlete, or sport that requires great performance in the CMJ, may consider adapting a warm-up or conditioning activity that includes depth jumps or band assisted jumps. Even the use of band resisted jumps elicits superior results than doing nothing at all, but this route is inferior to both depth jumps and band assisted.

Sports or environments like track and field, volleyball, NFL combine, and NBA combine all may benefit from these results. It would also be beneficial for future research to evaluate the long-term effects of such training measures.

References:

1. Seitz, L. B., & Haff, G. G. (2015). Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Body Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Medicine, 1-10.

2. Sheppard, J. M., Dingley, A. A., Janssen, I., Spratford, W., Chapman, D. W., & Newton, R. U. (2011). The effect of assisted jumping on vertical jump height in high-performance volleyball players. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 14(1), 85-89.

3. Tillin NA, Bishop D. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation and its Effect on Performance of Subsequent Explosive Activities. Sports Med. 39 (2): 147-166, 2009.

4. Rassier DE, MacIntosh BR. Coexistence of potentiation and fatigue in skeletal muscle. Braz. J. Med.Biol. Res. 33(5):499–508, 2000.

5. Rassier DE, MacIntosh BR. Coexistence of potentiation and fatigue in skeletal muscle. Braz. J. Med.Biol. Res. 33(5):499–508, 2000.

6. Christos, K. (2010). Post-activation potentiation: Factors affecting it and the effect on performance. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 28(3).

7. Verkhoshansky Y, Tetyan V. Speed-strength preparation of future champions. Legkaya Atleika. 2:12–13 , 1973.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed