Click to set custom HTML

The squat, a movement that most believe is a fundamental pattern to humans; a movement that we should strive to train and maintain for performance and just general wellness.

It is also a topic of much debate when it comes to HOW to perform a squat...

I've worked with close to a thousand athletes and guess what… they all squat differently. Different stance widths, different foot positions, different depths, different variation preferences, different bar positions, etc.

I'm tired of hearing athletes being told they MUST squat a certain way or there is only ONE way to squat… that is rubbish and certainly isn't rooted in science.

Let's think about this - do you really think someone 6'6 should squat the same as someone 5'2? Should someone with long femurs and a short torso squat the same as someone with short femurs and a long torso? Should someone with retroverted hips squat the same as someone with anteverted hips?

If I have a group of 20 athletes and had them all squat with a stance of their preference, to a depth they felt comfortable, with a toe angle that allows the most freedom - you know what I'd find? 20 different squats with different widths, foot angles, depths, trunk angles, etc.

So why do coaches & PT's still try to jam a square peg into a round hole by thinking there is only one way for people to squat? You NEED to squat with toes forward, in a shoulder-width stance, to a parallel depth!

Now I'm a man of science, not just anecdotal evidence, so let's see what some of the literature on anatomy and skeletal structure of the hips says and how this may effect the squat

It is COMMON that people squat with asymmetries and differences from side to side. It's normal to have someone feel and perform better with one toe angled out/in, staggered forward/backward, externally/internally rotated compared to the other.

If pain isn't present - THERE IS NOTHING WRONG WITH THIS - and it's likely aiding in performance, comfort, and health. We aren't symmetrical beings and sometimes forcing symmetry may actually be taking someone out of their "neutral".

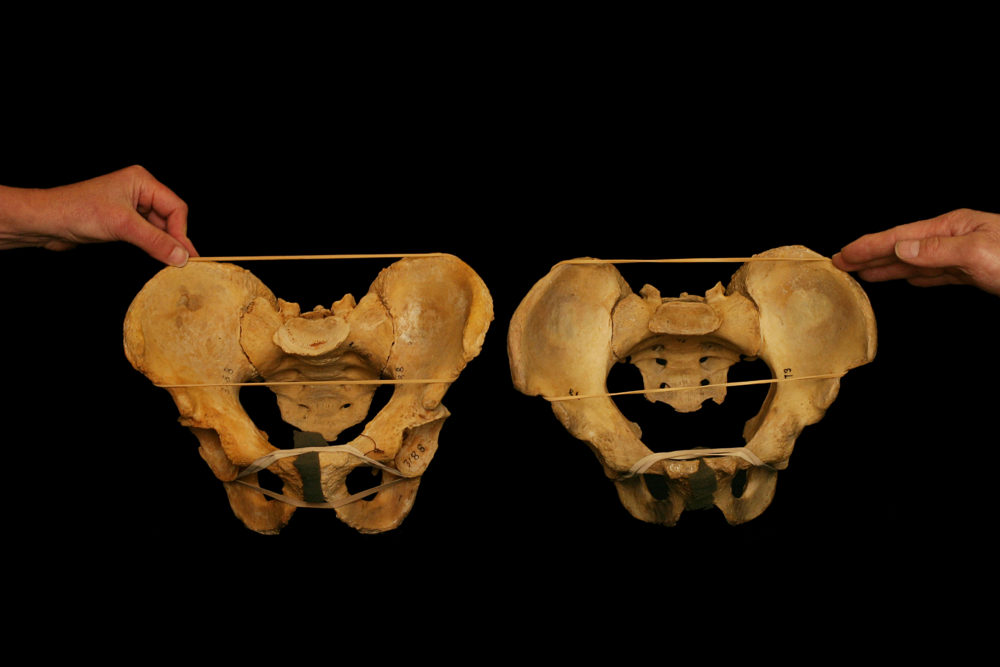

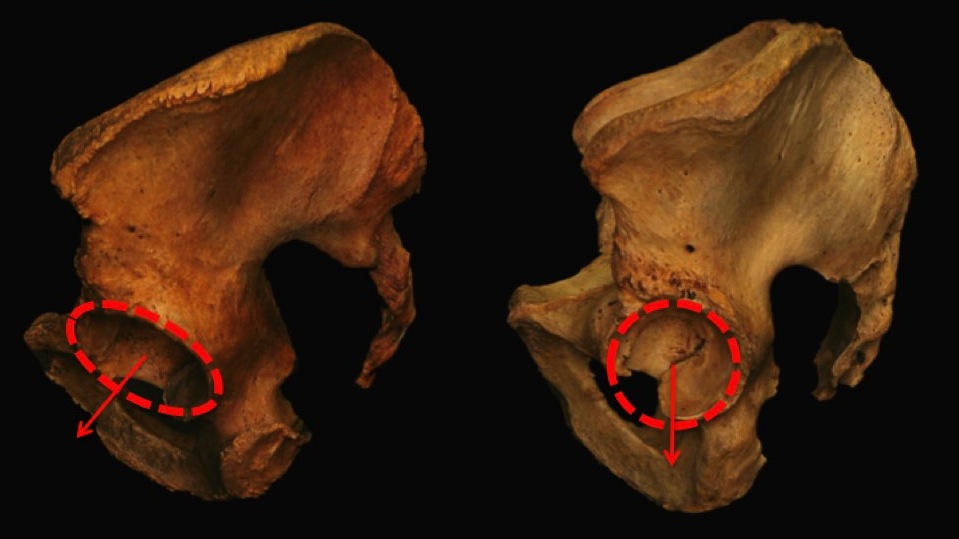

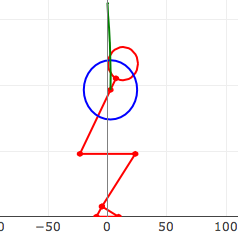

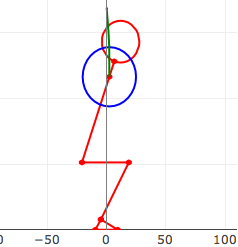

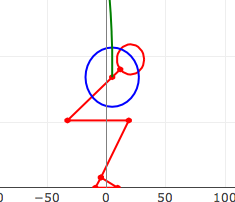

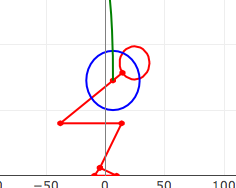

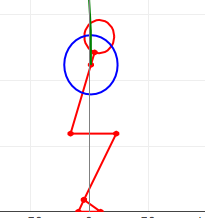

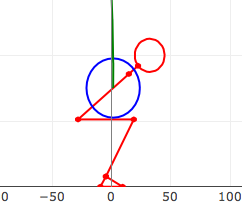

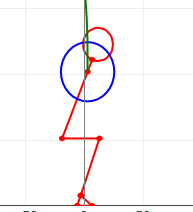

Want to see what these differences actually look like? Check out the below photos and see how these skeletal structures can differ and visualize how they'll dictate an athletes optimal squat.

It is also a topic of much debate when it comes to HOW to perform a squat...

- What stance?

- What width?

- What toe angle?

- What bar position?

- What variation?

- How deep?

I've worked with close to a thousand athletes and guess what… they all squat differently. Different stance widths, different foot positions, different depths, different variation preferences, different bar positions, etc.

I'm tired of hearing athletes being told they MUST squat a certain way or there is only ONE way to squat… that is rubbish and certainly isn't rooted in science.

Let's think about this - do you really think someone 6'6 should squat the same as someone 5'2? Should someone with long femurs and a short torso squat the same as someone with short femurs and a long torso? Should someone with retroverted hips squat the same as someone with anteverted hips?

If I have a group of 20 athletes and had them all squat with a stance of their preference, to a depth they felt comfortable, with a toe angle that allows the most freedom - you know what I'd find? 20 different squats with different widths, foot angles, depths, trunk angles, etc.

So why do coaches & PT's still try to jam a square peg into a round hole by thinking there is only one way for people to squat? You NEED to squat with toes forward, in a shoulder-width stance, to a parallel depth!

Now I'm a man of science, not just anecdotal evidence, so let's see what some of the literature on anatomy and skeletal structure of the hips says and how this may effect the squat

- The femoral neck/head isn't the same in every person. Zalawadia et al (2010) demonstrated that as much as 24-degrees difference in anteversion and retroversion is common. Zalawadia also noted that these differences of anteversion and retroversion can differ from side to side - not all hips are symmetrical!

- Laborie et al (2012) noted that anteversion and retroversion isn't strictly contained to the femoral head, it can also be present in the acetabulum. They looked at over 2000 samples of centre-edge angles of the acetabulum and found angles differed from 20.8-45 degrees

- Knutson (2005) looked at leg length, and found that about 90% people have a discrepancy with the average difference of about half a centimeter.

- Flanagan & Salem (2007) examined different kinetic variables in the squat of 18 experienced lifters. They looked at many things including average joint moments at the hip/knee/ankle, ground reaction forces in each foot, center of pressure for each foot, and maximum flexion angle at the knee/hip/ankle. They found many things (some statistically significant, others not) including side to side differences in center of pressure, ground reaction forces, and joint moments at the ankle, knee, and hip (especially the hip). The researchers concluded that NOBODY was balanced and every subject demonstrated differences in at least on of the joints (ankle, knee, hip)

It is COMMON that people squat with asymmetries and differences from side to side. It's normal to have someone feel and perform better with one toe angled out/in, staggered forward/backward, externally/internally rotated compared to the other.

If pain isn't present - THERE IS NOTHING WRONG WITH THIS - and it's likely aiding in performance, comfort, and health. We aren't symmetrical beings and sometimes forcing symmetry may actually be taking someone out of their "neutral".

Want to see what these differences actually look like? Check out the below photos and see how these skeletal structures can differ and visualize how they'll dictate an athletes optimal squat.

If we tried to take these people and squat them in a toes forward, shoulder width stance, to parallel, what do you think would happen?

Some would ace the test, while others would fail miserably… why?

Much of it would have to do with this structure - NOT some mobility, stability, strength, motor control dysfunction, but rather something they CANNOT change - their bone structure.

We seem to be in a stage where we see someone who can't squat deep, or prefers a wide stance, or turns their feet turn out, or has butt wink and we jump all over them with how their "insert joint/muscle" is tight/weak and needs soft-tissue, mobility, or activation work, BUT in many situations, no matter what correctives, or soft-tissue, or crazy mobility you throw at the athlete - they just won't be able to squat in certain positions.

Let's wet our whistle with a little more literature

So should everybody squat to parallel or ass to grass? Should everybody have the same stance width and toe angle?

NO!!!

Some have a tendency for hip flexion (squat deep), while others have tendency for hip extension. If we force them to parallel or ass to grass we may be forcing bone on bone or a hip impingement - not good things. The only people that NEED to squat to parallel are powerlfiters, it's a requirement of their sport. As for athletes, there is no rule book that says you have to squat to parallel or beyond - it's not a requirement nor is it going to make or break performance.

Again, ones ability to squat to different depths in different stances can be explained by their skeletal structure - NOT necessarily mobility or soft tissue or strength issues. It also means trying to say everybody should squat the SAME WAY is a terrible thought process and could actually be causing more harm than good.

Here's a quote from the great Stu McGill, considered the World's foremost expert on spinal health - "The most important matter on all of this is the depth of the hip socket. If people are looking up on the internet, depth of the hip socket and squat ability, they won’t find it. They have to go to the hip dysplasia literature. What they’ll find is that there are groups in the world with very shallow hip sockets (allow greater hip flexion) and some with deep hip sockets (make it difficult for deep hip flexion)."

Even the World's expert says it's structure that dictates deep squat ability, it's NOT some universal standard.

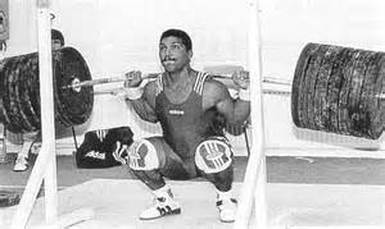

Insert pictures of strong peeps, lifting heavy things and what do you see?

Some would ace the test, while others would fail miserably… why?

Much of it would have to do with this structure - NOT some mobility, stability, strength, motor control dysfunction, but rather something they CANNOT change - their bone structure.

We seem to be in a stage where we see someone who can't squat deep, or prefers a wide stance, or turns their feet turn out, or has butt wink and we jump all over them with how their "insert joint/muscle" is tight/weak and needs soft-tissue, mobility, or activation work, BUT in many situations, no matter what correctives, or soft-tissue, or crazy mobility you throw at the athlete - they just won't be able to squat in certain positions.

Let's wet our whistle with a little more literature

- Elson and Aspinal (2008) showed what is tremendously obvious for coaches that actually work with people - there are vast differences in range of motion in hip flexion and extension - meaning some people are just better suited for deep hip flexion (deep squat), while this position would cause massive problems for others.

- D'Lima et al (200) demonstrated that differences in femoral neck/head thickness (as little as 2mm) could impact hip flexor ROM by 1.5-8.5 degrees.

- Lamontagne et al (2009) looked at people with femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI) and squat ability and concluded due to anatomical variations at the hip such as cam or pincer, there are plenty of lifters who will never be able to deep squat with proper form.

So should everybody squat to parallel or ass to grass? Should everybody have the same stance width and toe angle?

NO!!!

Some have a tendency for hip flexion (squat deep), while others have tendency for hip extension. If we force them to parallel or ass to grass we may be forcing bone on bone or a hip impingement - not good things. The only people that NEED to squat to parallel are powerlfiters, it's a requirement of their sport. As for athletes, there is no rule book that says you have to squat to parallel or beyond - it's not a requirement nor is it going to make or break performance.

Again, ones ability to squat to different depths in different stances can be explained by their skeletal structure - NOT necessarily mobility or soft tissue or strength issues. It also means trying to say everybody should squat the SAME WAY is a terrible thought process and could actually be causing more harm than good.

Here's a quote from the great Stu McGill, considered the World's foremost expert on spinal health - "The most important matter on all of this is the depth of the hip socket. If people are looking up on the internet, depth of the hip socket and squat ability, they won’t find it. They have to go to the hip dysplasia literature. What they’ll find is that there are groups in the world with very shallow hip sockets (allow greater hip flexion) and some with deep hip sockets (make it difficult for deep hip flexion)."

Even the World's expert says it's structure that dictates deep squat ability, it's NOT some universal standard.

Insert pictures of strong peeps, lifting heavy things and what do you see?

No identical stance, depth, toe angle, etc.

Why again do we try to force people to squat a certain way, to a certain depth? Coach athletes as individuals.

Let's look at some more myths that pertain to squatting

Knee's Can't Go Beyond The Toes

Here is another myth is purported in all areas and there’s little evidence to support this claim. The knees passing beyond the toes is not some universal point where all of a sudden the stresses on the knee become dangerous and every point before that is safe.

You know what's even more? Artificially restricting or trying to prevent forward movement of the knees may be detrimental to the hips and back. Fry et al (2003) looked at the effect of restricted squats where a wooden board was placed in front of the lifter that didn't allow the knees to track past the toes.

What did they find?

Why again do we try to force people to squat a certain way, to a certain depth? Coach athletes as individuals.

Let's look at some more myths that pertain to squatting

Knee's Can't Go Beyond The Toes

Here is another myth is purported in all areas and there’s little evidence to support this claim. The knees passing beyond the toes is not some universal point where all of a sudden the stresses on the knee become dangerous and every point before that is safe.

You know what's even more? Artificially restricting or trying to prevent forward movement of the knees may be detrimental to the hips and back. Fry et al (2003) looked at the effect of restricted squats where a wooden board was placed in front of the lifter that didn't allow the knees to track past the toes.

What did they find?

As expected, the board restricted setting reduced torque on the knees, but increased torque at the hip and low back. So you take stress on one joint, only to increase it at another - so pick your poison.

The researchers concluded, "Exercise technique guidelines should not be based primarily on force characteristics for only one involved joint (e.g., knees) while ignoring other anatomical areas (e.g., hips and low back).”

While shear forces have been shown to increase in the deep squat position with forward knees, the body can handle them appropriately without risk for injury (Schoenfeld (2010)). The most thorough review of squat depth on knee pain showed the demands on these tissues in a deep squat are well below the maximum that those tissues can withstand (Hartmann et al (2013)). What's important is not whether the knees go beyond the toes, but when they track beyond toes.

Plus, every Olympic lifter of all-time, theoretically should have messed up knees and some PT would tell them they're lifting wrong...

The researchers concluded, "Exercise technique guidelines should not be based primarily on force characteristics for only one involved joint (e.g., knees) while ignoring other anatomical areas (e.g., hips and low back).”

While shear forces have been shown to increase in the deep squat position with forward knees, the body can handle them appropriately without risk for injury (Schoenfeld (2010)). The most thorough review of squat depth on knee pain showed the demands on these tissues in a deep squat are well below the maximum that those tissues can withstand (Hartmann et al (2013)). What's important is not whether the knees go beyond the toes, but when they track beyond toes.

Plus, every Olympic lifter of all-time, theoretically should have messed up knees and some PT would tell them they're lifting wrong...

Squat Stance and Squat Variation

Guess what - the type of squat you use isn't vastly different from each other. EMG between a front squat and back squat aren't that different, with some studies even showing NO STATISTICAL DIFFERENCE in muscle activities between front and back squats. (Contreras et al (2016); Gullet et al (2009)). In general, the front squat will lead to slightly more quad activation and thoracic extension strength; while back squat slightly more glute/hamstring activation, but again, the EMG difference between the two isn't as big as people think.

How about wide stance vs narrow stance?

Wide stance squats tends to activate greater adductor and glute compared to narrow squat, with no difference between quad activation (Escamilla et al. (2001); Paoli et al (2009); Steven & Donald (1999)). Swinton et al (2012) recently demonstrated exactly this as the researchers showed EMG results for glute activation were significantly higher in a wide stance compared to a narrow stance. These EMG results also showed that quadricep activation between the stances were identical - concluding, muscle activation wise, a narrow stance isn't superior to a wide stance.

How about toe angle or hip angle?

Ninos et al. (1997) found no difference in vastus medialis activation between barbell back squats with two different hip rotation angles (feet pointing outwards vs. feet pointing forwards). While, Pereira et al (2010) found externally rotating the hip to 30 and 50-degrees resulted in greater hip adductor activation with no change in rectus femoris activation, leading the researchers to conclude that squatting to 60-90 degrees of knee flexion with 30 degrees of external rotation maximized muscle activation.

Again, there is NO LITERATURE supporting the NEED to squat with toes forward! Rather than squatting with your toes forward or pointed out to a predetermined degree and forcing your knees and hips to follow along, you’re better off seeing what hip and knee position feels the strongest and most comfortable, and letting that determine how far out you point your feet (Nuckols (2016))

In a great review of all the variables that effect muscle activation of a loaded back squat, Clark et al (2012) concluded, research of common variations such as stance width, hip rotation, and squat variation (front vs back) do not significantly affect muscle activation. Turning the toes out, however, only changes the activation of the adductor muscle group. The glutes and quads (the main movers in the squat) are not significantly activated to a greater extent by any of the variables (Clark at el (2012)).

So we've seen, specific squat variations - wide, narrow, toes forward, toes out, depth - aren't make or break factors when it comes to muscle activation, joint stress, or performance.

So again, why would be ever think there is only one way to squat and what would make this way superior? The fact is, there isn't a single strategy to squat and instead should be dictated upon by the individuals unique skeletal structure, limb lengths, past injury history, mobility/stability factors, and biomechanics.

Here's just a small list of things that influence squat mechanics

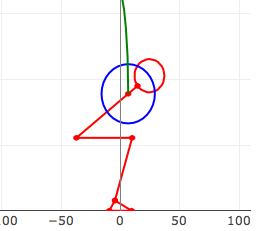

Linked below is a really cool website that demonstrates how different body part lengths, stance width, bar positioning, etc effect the outcome of what a squat will look like - again it's basic biomechanics - http://mysquatmechanics.com

Here are some pictures of how simply changing levers, stance width, ankle mobility, and bar position effect the end look of a squat

Guess what - the type of squat you use isn't vastly different from each other. EMG between a front squat and back squat aren't that different, with some studies even showing NO STATISTICAL DIFFERENCE in muscle activities between front and back squats. (Contreras et al (2016); Gullet et al (2009)). In general, the front squat will lead to slightly more quad activation and thoracic extension strength; while back squat slightly more glute/hamstring activation, but again, the EMG difference between the two isn't as big as people think.

How about wide stance vs narrow stance?

Wide stance squats tends to activate greater adductor and glute compared to narrow squat, with no difference between quad activation (Escamilla et al. (2001); Paoli et al (2009); Steven & Donald (1999)). Swinton et al (2012) recently demonstrated exactly this as the researchers showed EMG results for glute activation were significantly higher in a wide stance compared to a narrow stance. These EMG results also showed that quadricep activation between the stances were identical - concluding, muscle activation wise, a narrow stance isn't superior to a wide stance.

How about toe angle or hip angle?

Ninos et al. (1997) found no difference in vastus medialis activation between barbell back squats with two different hip rotation angles (feet pointing outwards vs. feet pointing forwards). While, Pereira et al (2010) found externally rotating the hip to 30 and 50-degrees resulted in greater hip adductor activation with no change in rectus femoris activation, leading the researchers to conclude that squatting to 60-90 degrees of knee flexion with 30 degrees of external rotation maximized muscle activation.

Again, there is NO LITERATURE supporting the NEED to squat with toes forward! Rather than squatting with your toes forward or pointed out to a predetermined degree and forcing your knees and hips to follow along, you’re better off seeing what hip and knee position feels the strongest and most comfortable, and letting that determine how far out you point your feet (Nuckols (2016))

In a great review of all the variables that effect muscle activation of a loaded back squat, Clark et al (2012) concluded, research of common variations such as stance width, hip rotation, and squat variation (front vs back) do not significantly affect muscle activation. Turning the toes out, however, only changes the activation of the adductor muscle group. The glutes and quads (the main movers in the squat) are not significantly activated to a greater extent by any of the variables (Clark at el (2012)).

So we've seen, specific squat variations - wide, narrow, toes forward, toes out, depth - aren't make or break factors when it comes to muscle activation, joint stress, or performance.

So again, why would be ever think there is only one way to squat and what would make this way superior? The fact is, there isn't a single strategy to squat and instead should be dictated upon by the individuals unique skeletal structure, limb lengths, past injury history, mobility/stability factors, and biomechanics.

Here's just a small list of things that influence squat mechanics

- Foot Wear (elevated heel vs flat heel)

- Long Tibia vs Short Femur

- Short Tibia vs Long Femur

- Short Femur vs Long Torso

- Long Femur vs Short Torso

- Body Mass

- Stance Width

- Toe Angle

- Foot Size (Length)

- Cueing

- Anterior vs Posterior Chain Strength

- Specific Joint Mobility and Stability Strengths and Weaknesses

- Bar Position

Linked below is a really cool website that demonstrates how different body part lengths, stance width, bar positioning, etc effect the outcome of what a squat will look like - again it's basic biomechanics - http://mysquatmechanics.com

Here are some pictures of how simply changing levers, stance width, ankle mobility, and bar position effect the end look of a squat

All-In-All

The goal of this article is to demonstrate there is no universal way to squat and we need to work to allow and find our athletes optimal way to squat based on their individual anatomy, levers, mobility/stability needs, past injury history, etc - and NOT try to pigeon-hole everybody into a certain way of squatting.

Please share this with anybody you think would benefit and let's stop the squat stupidity from spreading.

PS - Below are some squat assessment videos on what we might use to assess our athletes to find their best squatting stance.

The goal of this article is to demonstrate there is no universal way to squat and we need to work to allow and find our athletes optimal way to squat based on their individual anatomy, levers, mobility/stability needs, past injury history, etc - and NOT try to pigeon-hole everybody into a certain way of squatting.

Please share this with anybody you think would benefit and let's stop the squat stupidity from spreading.

PS - Below are some squat assessment videos on what we might use to assess our athletes to find their best squatting stance.

References:

Clark, D. R., Lambert, M. I., & Hunter, A. M. (2012). Muscle activation in the loaded free barbell squat: a brief review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(4), 1169-1178.

Contreras, B., Vigotsky, A. D., Schoenfeld, B. J., Beardsley, C., & Cronin, J. (2016). A comparison of gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and vastus lateralis electromyography amplitude in the parallel, full, and front squat variations in resistance-trained females. Journal of applied biomechanics, 32(1), 16-22.

Escamilla, R. F., Fleisig, G. S., Lowry, T. M., Barrentine, S. W., & Andrews, J. R. (2001). A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of the squat during varying stance widths. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 33(6), 984-998.

Flanagan, S. P., & Salem, G. J. (2007). BILATERAL DIFFERENCES IN THE NET JOINT TORQUES DURING THE SQUAT EXERCIS. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 21(4), 1220-1226.

Gullett, J. C., Tillman, M. D., Gutierrez, G. M., & Chow, J. W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 284-292.

Hartmann, H., Wirth, K., & Klusemann, M. (2013). Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load. Sports medicine, 43(10), 993-1008.

Knutson, G. A. (2005). Anatomic and functional leg-length inequality: a review and recommendation for clinical decision-making. Part I, anatomic leg-length inequality: prevalence, magnitude, effects and clinical significance. Chiropractic & osteopathy, 13(1), 1.

Lamontagne, M., Kennedy, M. J., & Beaulé, P. E. (2009). The effect of cam FAI on hip and pelvic motion during maximum squat. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 467(3), 645-650.

Ninos, J. C., Irrgang, J. J., Burdett, R., & Weiss, J. R. (1997). Electromyographic analysis of the squat performed in self-selected lower extremity neutral rotation and 30 of lower extremity turn-out from the self-selected neutral position. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 25(5), 307-315.

Nuckols, Greg. http://strengtheory.com/how-to-squat/. 2016

Paoli, A., Marcolin, G., & Petrone, N. (2009). The effect of stance width on the electromyographical activity of eight superficial thigh muscles during back squat with different bar loads. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 246-250.

Pereira, G. R., Leporace, G., das Virgens Chagas, D., Furtado, L. F., Praxedes, J., & Batista, L. A. (2010). Influence of hip external rotation on hip adductor and rectus femoris myoelectric activity during a dynamic parallel squat. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2749-2754.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3497-3506.

Steven, T. M., & Donald, R. M. (1999). Stance width and bar load effects on leg muscle activity during the parallel squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 31, 428-436.

Swinton PA, et al (2012) A Biomechanical Comparison of the Traditional Squat, Powerlifting Squat, and Box Squat. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 26(7):1805–16

Clark, D. R., Lambert, M. I., & Hunter, A. M. (2012). Muscle activation in the loaded free barbell squat: a brief review. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 26(4), 1169-1178.

Contreras, B., Vigotsky, A. D., Schoenfeld, B. J., Beardsley, C., & Cronin, J. (2016). A comparison of gluteus maximus, biceps femoris, and vastus lateralis electromyography amplitude in the parallel, full, and front squat variations in resistance-trained females. Journal of applied biomechanics, 32(1), 16-22.

Escamilla, R. F., Fleisig, G. S., Lowry, T. M., Barrentine, S. W., & Andrews, J. R. (2001). A three-dimensional biomechanical analysis of the squat during varying stance widths. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 33(6), 984-998.

Flanagan, S. P., & Salem, G. J. (2007). BILATERAL DIFFERENCES IN THE NET JOINT TORQUES DURING THE SQUAT EXERCIS. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 21(4), 1220-1226.

Gullett, J. C., Tillman, M. D., Gutierrez, G. M., & Chow, J. W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 284-292.

Hartmann, H., Wirth, K., & Klusemann, M. (2013). Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load. Sports medicine, 43(10), 993-1008.

Knutson, G. A. (2005). Anatomic and functional leg-length inequality: a review and recommendation for clinical decision-making. Part I, anatomic leg-length inequality: prevalence, magnitude, effects and clinical significance. Chiropractic & osteopathy, 13(1), 1.

Lamontagne, M., Kennedy, M. J., & Beaulé, P. E. (2009). The effect of cam FAI on hip and pelvic motion during maximum squat. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 467(3), 645-650.

Ninos, J. C., Irrgang, J. J., Burdett, R., & Weiss, J. R. (1997). Electromyographic analysis of the squat performed in self-selected lower extremity neutral rotation and 30 of lower extremity turn-out from the self-selected neutral position. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 25(5), 307-315.

Nuckols, Greg. http://strengtheory.com/how-to-squat/. 2016

Paoli, A., Marcolin, G., & Petrone, N. (2009). The effect of stance width on the electromyographical activity of eight superficial thigh muscles during back squat with different bar loads. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(1), 246-250.

Pereira, G. R., Leporace, G., das Virgens Chagas, D., Furtado, L. F., Praxedes, J., & Batista, L. A. (2010). Influence of hip external rotation on hip adductor and rectus femoris myoelectric activity during a dynamic parallel squat. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2749-2754.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(12), 3497-3506.

Steven, T. M., & Donald, R. M. (1999). Stance width and bar load effects on leg muscle activity during the parallel squat. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 31, 428-436.

Swinton PA, et al (2012) A Biomechanical Comparison of the Traditional Squat, Powerlifting Squat, and Box Squat. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 26(7):1805–16

RSS Feed

RSS Feed