For anyone that has done research or submitted to a journal, knows the amount of time, detail, revisions, and head-ache that goes into writing and researching for a paper.

Writing a proposal, getting proposal approval, getting IRB approval, collecting subjects, data collection, data analysis, submission to journals, rejection, another submission, revisions, re-submission, more revisions, re-submission, and finally acceptance. This process can take anywhere fem 6-18months from start to finish; not to mention the tons of stress and time and loss of confidence that comes from writing, sifting through hundreds of research articles, inevitable rejection, double digit revisions, and wondering if your work will ever be accepted.

For those of us who are full-time coaches, it is difficult to find the time and energy to dedicate to this type of consistent research.

With that being said, I do think every S&C coach should strive to produce a real scientific paper and be published by a journal.

There are a couple of reasons for this.

While I do enjoy the process and the opportunity to have work published, I also know there is simply not enough hours in the day to get all the data I track published into a journal.

So instead, I will label articles in this section as BBA Journal of Sports Performance. This will be where I can dump research that we're conducting at BBA, but aren't working to get published into a journal.

With that being said, this work will all be conducted in a scientific manner - clean procedures, proper set-up, detailed data collection, and inferential data analysis. There will be less detailed introductions and discussions - just want to present the data with a few closing thoughts.

The overall goal is for this data to be more than anecdotal or what another pet peeve of mine is when coaches say, "We've seen great results from INSERT EXERCISE/TOOL/MODALITY". Yet, they cannot produce results, a control group, or inferential statistics to validate their claims.

So without further ado, let's go into this BBA Journal Study.

Writing a proposal, getting proposal approval, getting IRB approval, collecting subjects, data collection, data analysis, submission to journals, rejection, another submission, revisions, re-submission, more revisions, re-submission, and finally acceptance. This process can take anywhere fem 6-18months from start to finish; not to mention the tons of stress and time and loss of confidence that comes from writing, sifting through hundreds of research articles, inevitable rejection, double digit revisions, and wondering if your work will ever be accepted.

For those of us who are full-time coaches, it is difficult to find the time and energy to dedicate to this type of consistent research.

With that being said, I do think every S&C coach should strive to produce a real scientific paper and be published by a journal.

There are a couple of reasons for this.

- We have access to real, high level athletes - something a lot of research is missing

- Give back and further the education of our field

- Appreciate and understand of how difficult, tedious, and in-depth research can be. It's a pet peeve of mine when coaches, who have never published research, criticize those that do. You'll be humbled when you go through this process

While I do enjoy the process and the opportunity to have work published, I also know there is simply not enough hours in the day to get all the data I track published into a journal.

So instead, I will label articles in this section as BBA Journal of Sports Performance. This will be where I can dump research that we're conducting at BBA, but aren't working to get published into a journal.

With that being said, this work will all be conducted in a scientific manner - clean procedures, proper set-up, detailed data collection, and inferential data analysis. There will be less detailed introductions and discussions - just want to present the data with a few closing thoughts.

The overall goal is for this data to be more than anecdotal or what another pet peeve of mine is when coaches say, "We've seen great results from INSERT EXERCISE/TOOL/MODALITY". Yet, they cannot produce results, a control group, or inferential statistics to validate their claims.

So without further ado, let's go into this BBA Journal Study.

COMPARISON OF 1x20 TRAINING PROGRAM vs A TRADITIONAL TRAINING PROGRAM

IN BASEBALL PITCHERS

IN BASEBALL PITCHERS

INTRODUCTION:

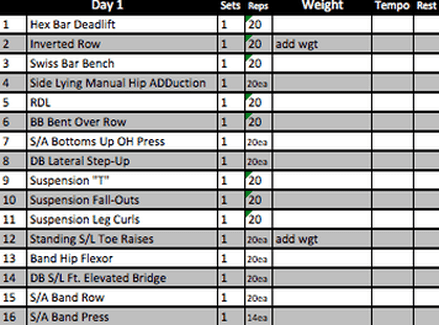

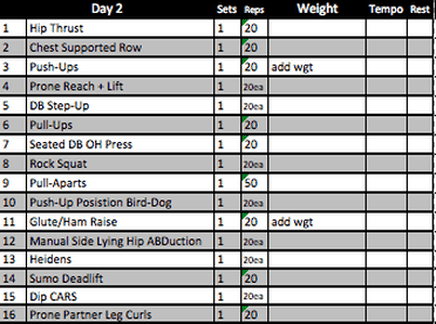

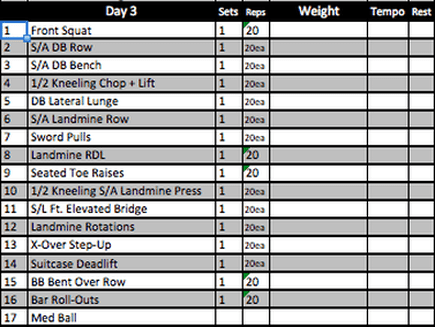

The 1x20 program/philosophy was popularized by Dr. Michael Yessis. The premise: 15-25 exercises, using one set of 20 repetitions for each exercise. The goal is to try and hit just about every joint action - so the program involves both multi-joint and single-joint movements in every program. The philosophy is also to progress from more general exercise selection to more specific exercise selection as the athlete demonstrate amplitude and competency.

The rationale is each day the athlete gets exposed to a variety of movement patterns, build movement competency under managable loads, allow better ligamentous/tendon adaptations, develops both opportunities for GPP and SPP, and it allows for the minimal effective dose.

The program consists of certain weeks of 1x20, the progressing to 1x14, and finally 1x8 as the athletes need further, more specific adaptations towards specific physical capabilities

It has gained popularity with many coaches as a quality model for GPP and for times when coaches are short on time. A typical session may last only 25-45min, depending on how many movements you have included. Another proposed benefit of the 1x20, is because the sessions are short and sweet, and don't elicit substantional tissue damage or DOMS, you can train more frequently. These benefits allow for more efficient and effective adaptations for athletes.

These benefits have been shared anecodotely by coaches, but no research has been done to verify these results in a controlled trial.

SUBJECTS:

Seventeen male, collegiate baseball pithcers (Age=19.5 years) parook in this study. Subjects were split into 2-groups; 1x20 Program (n=8) and Traditional Program (n=9). Participants all had at least 1-year of resistance training experience in a S&C program (n=2.7 years)

PROCEDURES:

Particpants were split into 2-groups; 1x20 Training Program (n=8) and Traditional Program (n=9). All participants underwent pre-testing in the following tests, in the specific order, with the number of trials included in parenthesis

Athletes partook in three training sessions per week for 9-weeks (27 total training sessions). The 1x20 Training Program progressed from 4-weeks of 1x20, 3-weeks of 1x14, and 2-weeks of 1x8.

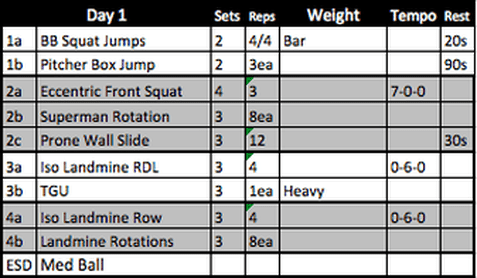

The "Traditional" Training (What I would traditinally plan for my pitchers, hence the traditional tag) progressed from a 3-week block of hypertrophy, 3-week block of eccentric and isometric, and 3-week block of power and specificity of transfer. A similar series that has been used with this pitching staff for the previous 3-years.

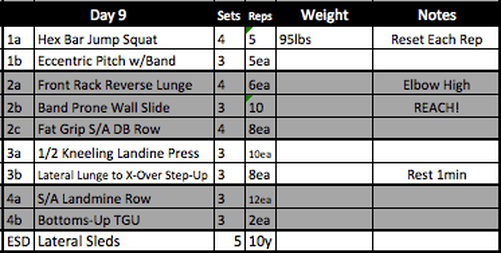

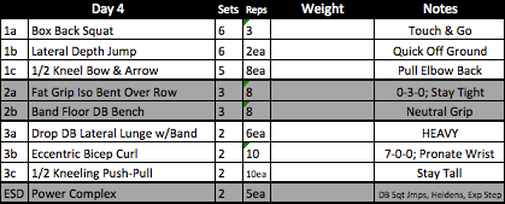

Examples of the training programs are included below for reference.

The 1x20 program/philosophy was popularized by Dr. Michael Yessis. The premise: 15-25 exercises, using one set of 20 repetitions for each exercise. The goal is to try and hit just about every joint action - so the program involves both multi-joint and single-joint movements in every program. The philosophy is also to progress from more general exercise selection to more specific exercise selection as the athlete demonstrate amplitude and competency.

The rationale is each day the athlete gets exposed to a variety of movement patterns, build movement competency under managable loads, allow better ligamentous/tendon adaptations, develops both opportunities for GPP and SPP, and it allows for the minimal effective dose.

The program consists of certain weeks of 1x20, the progressing to 1x14, and finally 1x8 as the athletes need further, more specific adaptations towards specific physical capabilities

It has gained popularity with many coaches as a quality model for GPP and for times when coaches are short on time. A typical session may last only 25-45min, depending on how many movements you have included. Another proposed benefit of the 1x20, is because the sessions are short and sweet, and don't elicit substantional tissue damage or DOMS, you can train more frequently. These benefits allow for more efficient and effective adaptations for athletes.

These benefits have been shared anecodotely by coaches, but no research has been done to verify these results in a controlled trial.

SUBJECTS:

Seventeen male, collegiate baseball pithcers (Age=19.5 years) parook in this study. Subjects were split into 2-groups; 1x20 Program (n=8) and Traditional Program (n=9). Participants all had at least 1-year of resistance training experience in a S&C program (n=2.7 years)

PROCEDURES:

Particpants were split into 2-groups; 1x20 Training Program (n=8) and Traditional Program (n=9). All participants underwent pre-testing in the following tests, in the specific order, with the number of trials included in parenthesis

- Vertical Jump (3)

- Broad Jump (3)

- Single Leg Lateral Jump (2 each)

- 20-Yard Dash (3)

- Throwing Velocity - Crow Hop (5)

Athletes partook in three training sessions per week for 9-weeks (27 total training sessions). The 1x20 Training Program progressed from 4-weeks of 1x20, 3-weeks of 1x14, and 2-weeks of 1x8.

The "Traditional" Training (What I would traditinally plan for my pitchers, hence the traditional tag) progressed from a 3-week block of hypertrophy, 3-week block of eccentric and isometric, and 3-week block of power and specificity of transfer. A similar series that has been used with this pitching staff for the previous 3-years.

Examples of the training programs are included below for reference.

RESULTS:

Athletes were omitted from having their results included in the study if they missed 3 or more sessions. Two athletes were omitted from the results, thus only the results from 17 athletes were used.

The use of paired T-Tests were used to test within and between each experimental groups to determine significance (p=0.05).

Within Groups

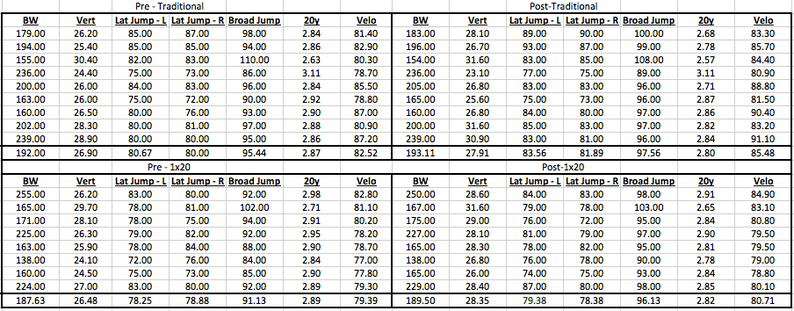

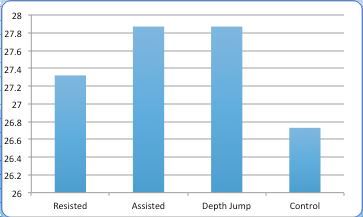

Comparing the 1x20 Program vs the Traditional Program we see no significant difference in results with the vertical jump, lateral jump (left), or 20y dash. There was significant difference between the broad jump (1x20 superior), lateral jump (right)(traditional superior), and velo (traditional superior).

(All results are shown below in table)

Athletes were omitted from having their results included in the study if they missed 3 or more sessions. Two athletes were omitted from the results, thus only the results from 17 athletes were used.

The use of paired T-Tests were used to test within and between each experimental groups to determine significance (p=0.05).

Within Groups

- Traditional Group - Vertical Jump = (p=.058)

- Traditional Group - Broad Jump = (p=.042)

- Traditional Group - Lateral Jump - L = (p=.014)

- Traditional Group - Lateral Jump - R = (p=.001)

- Traditional Group - 20y Dash = (p=.004)

- Traditional Group - Velo = (p=.00)

- 1x20 Group - Vertical Jump = (p=.00)

- 1x20 Group - Broad Jump = (p=.001)

- 1x20 - Lateral Jump - L = (p=.185)

- 1x20 - Lateral Jump - R = (p=.598)

- 1x20 Group - 20y Dash = (p=.00)

- 1x20 Group - Velo = (p=.001)

- Vertical = (p=.11)

- Broad Jump = (p=.03) (*1x20)

- Lateral Jump - R = (p=.02) (*Traditional)

- Lateral Jump - L = (p=.14)

- 20y Dash = (p=.82)

- Velo = (p=.00) (*Traditional)

Comparing the 1x20 Program vs the Traditional Program we see no significant difference in results with the vertical jump, lateral jump (left), or 20y dash. There was significant difference between the broad jump (1x20 superior), lateral jump (right)(traditional superior), and velo (traditional superior).

(All results are shown below in table)

DISCUSSION

Looking at the results, you'll see the 1x20 program resulted in similar, if not better, outcomes in vertical, broad jump, and 20-yard sprinting speed compared to the traditional program. Where it fell short was with specificity and transfer to the demands of the sport. The traditional program, which was geared towards baseball pitchers - significantly enhanced lateral jumping ability, and pitching velocity compared to the 1x20 group.

So, on one end we have 1x20 as a very valuable GPP or general strength program; one that takes less time and greater efficiency. On the other end, we have a lack of specificity or transfer to the specific task of the athletes. Now, one of the aspects of the 1x20 Dr. Yessis purposes is the use of Specific Physical Preparation exercises - so maybe I just didn't do a good enough job of introducing SPP movements into the program compared to the traditional group.

I'm a big fan of using SPP movements and transitioning the weight room for specific coordination, motor learning, and transfer to the actual demands of the sport. Strength, power, and velocity is much more than just a squat or Olympic lift - it's coordinating muscle activation, movement patterns, joint actions - Specificity and coordination is key to power output and force production. It becomes less and less important to make muscles stronger if the athlete never needs to display all that strength in the field of play. Make the athlete strong enough for their sport and then develop methods that allow them to improve muscle coordination and rhythm - and maybe I didn't program better SPP exercises for the 1x20 group, but this group lagged behind the traditional group in terms of enhancing on the mound throwing velocity and power/speed in the frontal plane.

Before starting this program, one of my worries was that the athletes in the 1x20 group would get bored and lose interest/motivation of doing the same things, everyday, every week for the duration of the program. Fortunately, this did not happen, and there was no complacency or loss of motivation in the athletes - in fact, they seemed to take to the task and utilize the extra time at the end for more recovery/individual modalities while the traditional group finished up.

At the end of the day, I came away very impressed with the results of the 1x20. I was very skeptical going into this, and doubted this type of program could elicit results that would be comparable to what I would traditionally program. That being said, I have further developed the 1x20 program and have used it as an introductory program for many athletes, but I do not think it will replace more specific, traditional type of training for my athletes. The end goal is transfer to the field of play - not just pounds lifted or vertical jump. The weight room needs to be seen as a method of developing specific coordination, sequencing, timing, rhythm, and motor learning that will transfer to the field of play - not just as a place for strength, hypertrophy, power. Overall, I encourage others to test the 1x20, as currently, there is no literature looking at the 1x20 as a means of strength, hypertrophy, power, speed, tendon strength, transfer, etc. That will be the next step in 1x20 - an actual research study, but I'm am now optimisitic about it and have seen benefits from implementing it.

Looking at the results, you'll see the 1x20 program resulted in similar, if not better, outcomes in vertical, broad jump, and 20-yard sprinting speed compared to the traditional program. Where it fell short was with specificity and transfer to the demands of the sport. The traditional program, which was geared towards baseball pitchers - significantly enhanced lateral jumping ability, and pitching velocity compared to the 1x20 group.

So, on one end we have 1x20 as a very valuable GPP or general strength program; one that takes less time and greater efficiency. On the other end, we have a lack of specificity or transfer to the specific task of the athletes. Now, one of the aspects of the 1x20 Dr. Yessis purposes is the use of Specific Physical Preparation exercises - so maybe I just didn't do a good enough job of introducing SPP movements into the program compared to the traditional group.

I'm a big fan of using SPP movements and transitioning the weight room for specific coordination, motor learning, and transfer to the actual demands of the sport. Strength, power, and velocity is much more than just a squat or Olympic lift - it's coordinating muscle activation, movement patterns, joint actions - Specificity and coordination is key to power output and force production. It becomes less and less important to make muscles stronger if the athlete never needs to display all that strength in the field of play. Make the athlete strong enough for their sport and then develop methods that allow them to improve muscle coordination and rhythm - and maybe I didn't program better SPP exercises for the 1x20 group, but this group lagged behind the traditional group in terms of enhancing on the mound throwing velocity and power/speed in the frontal plane.

Before starting this program, one of my worries was that the athletes in the 1x20 group would get bored and lose interest/motivation of doing the same things, everyday, every week for the duration of the program. Fortunately, this did not happen, and there was no complacency or loss of motivation in the athletes - in fact, they seemed to take to the task and utilize the extra time at the end for more recovery/individual modalities while the traditional group finished up.

At the end of the day, I came away very impressed with the results of the 1x20. I was very skeptical going into this, and doubted this type of program could elicit results that would be comparable to what I would traditionally program. That being said, I have further developed the 1x20 program and have used it as an introductory program for many athletes, but I do not think it will replace more specific, traditional type of training for my athletes. The end goal is transfer to the field of play - not just pounds lifted or vertical jump. The weight room needs to be seen as a method of developing specific coordination, sequencing, timing, rhythm, and motor learning that will transfer to the field of play - not just as a place for strength, hypertrophy, power. Overall, I encourage others to test the 1x20, as currently, there is no literature looking at the 1x20 as a means of strength, hypertrophy, power, speed, tendon strength, transfer, etc. That will be the next step in 1x20 - an actual research study, but I'm am now optimisitic about it and have seen benefits from implementing it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed